BGHS.NEWS

Reconciling academia and professional practice

Reconciling academia and professional practice

Practical Projects at the BGHS

(Figure 1: Poster of the Discussion)

80 to 90 percent of researchers with a doctorate will not work as employees in academic research in the long term. This fact has been scandalised for years and solutions are primarily demanded from the universities, for example by creating more permanent positions alongside professorships and predictable career paths. As right as these efforts are, they will not change anything significant about the fact that the vast majority of young researchers leave academic science sooner or later. It does little good to suppress this fact; it must be given more attention, both by doctoral researchers and supervisors. And perspectives must be developed that link academic science and the non-academic world. This is the quintessence of the panel discussion on the topic of “Transitions between doing a doctorate and profession”, which took place at the BGHS on 10 November 2022.

Over the past four years, the BGHS has embarked on a new path that has enabled doctoral researchers in the humanities and social sciences to gain practical experience in the non-university professional world while focusing on their own interests and skills. In the pilot project “Non-University Careers”, which is funded from the rectorate's strategy budget from 2019 to 2022, doctoral researchers at the BGHS were able to apply for practical projects in cooperation with a non-university practical partner, which were funded by three-month scholarships. A total of eleven projects were carried out, and the last two are nearing completion. At the event, Marie Kaiser, the current Vice-rector for Personnel Development and Gender Equality, and Martin Egelhaaf, the former Vice-rector for Research, Young Researchers and Gender Equality, discussed with Gladys Vásquez and Yannick Schöpper, doctoral researchers and scholarship holders in the programme, as well as Ulf Ortmann, the programme coordinator, what experience has been gained in the programme and what this means for Bielefeld University's activities in the area of (non-university) careers.

When asked by moderator Ulf Ortmann how the BGHS’s project application was approved in 2018, Martin Egelhaaf reminded the audience of the “Tenure Track Programme”, which was launched by the German federal and state governments in 2016 to create 1,000 additional professorships for young researchers. To apply for these tenure-track professorships, Bielefeld University had to create a personnel development concept for the young researchers and also address the fact that not all of them can stay in academic science. And in this situation, the BGHS application fell on “fertile ground”, according to Martin Egelhaaf.

Yannick Schöpper is one of the scholarship holders who were able to carry out a practical project. He cooperated with the Agentur für Erneuerbare Energien e.V. (AEE).

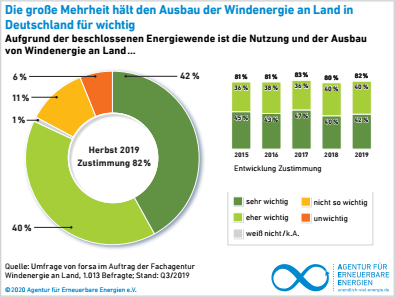

(Figure 2: Results of the Study)

He gave a lively account of how he had dug deep into the theory of his political

science doctoral project before starting the project and was then confronted

with the empirical field in the practical project. The big challenge in

applying for the project was to find a topic that was connectable to

professional practice perspectives and had a relevance that was not only

scientific but also social. And his choice fell on the question of how local

acceptance of onshore wind turbines is, which he illuminated in a very readable

background paper for the AEE. “The direct contact with empiricism has clearly broadened

my perspective and this has also changed the dissertation project,” he summed

up positively. (Link to the Report)

Historian Gladys Vásquez also described the positive experiences she had during her practical project. When she applied for the project, her (doctoral) thesis had just expired and she was also thinking about her professional future in addition to working on her dissertation. She had already worked in the field of public history in Peru before her doctorate and wanted to return to this professional field. “Doing the academic work, I had forgotten some of my qualifications,” Gladys Vásquez recalled. But she also lacked a corresponding network in Germany. During a scientific symposia, she met her future project partners from “Kuskalla Abya Yala”, an NGO dedicated to the revival of Quechua, a widespread indigenous language family in America.

(Figure 3: Most spoken indigenous languages, Copyright: Gladys Vasquez)

This contact with the researchers of “Kuskalla Abya

Yala”, who are also activists, made her aware of the social relevance of their

work. And so she organised a joint workshop on the experiences and practices of

efforts to disseminate Quechua languages. The biggest challenge was to

communicate with the activists in the field, who did not always have access to

the internet or even the telephone. Almost unimaginable in our supposedly

digitalised world. Gladys Vásquez said she had become more realistic as a

result of the project. “I want a job that fulfils me.” And she is more likely

to find that outside the university, of course after completing her dissertation. (Link to the Report)

Marie Kaiser was impressed by the stories of the two doctoral researchers about their experiences in the practical projects. The university should not be a ‘bubble’, but what the scholars do must have relevance for the professional fields, she emphasised the aspect of knowledge transfer through the practical projects. In the discussion with the audience, it became clear that there are already many offers at Bielefeld University, for example from the Career Service and the personnel development for researchers. But, according to Marie Kaiser, counselling is something different from practical experience. “We have to think about that.”

The fact that the practical projects not only enable experience in professional fields, but also bring something to the content of the doctoral theses, as Yannick Schöpper told us, was a surprise for Martin Egelhaaf. It was questionable, however, whether this applied equally to all dissertation topics, for example, also to very theoretical work. On the other hand, there was no question for him that the concept of practical projects is transferable to other fields, for example to the natural sciences. Thus, it could be beneficial for applications for collaborative projects, which always have to address the promotion of non-university careers. The question of whether and how such a programme could be set up university-wide remained open.

The event “Transitions between doing a doctorate and profession” showed in how many areas Bielefeld University already offers a wide variety of support formats for young researchers in their academic and non-academic careers. But it also showed that the special format of scholarship-funded practical projects, which was developed and tested in the pilot project “Non-University Careers” at the BGHS, very successfully fills an existing gap. The development and implementation of a project lasting several months in cooperation with a non-university partner, which is based on the skills and interests of the young researchers, enables practical professional experience that is closely related to their own academic training. At the same time, it allows them to examine the social relevance of their own doctoral project and to develop their academic work accordingly. In this way, the practical projects also contribute to a considerable degree to the mutual transfer of knowledge between academic science and professional practice. They show: Science and non-university professional practice are not contradictory, they are reconcilable.

Sabine Schäfer

Here you can find more Reports about the Practical Projects.