BGHS.NEWS

Reports about Practical Projects #7

:: Non-academic careers::

Reports about Practical Projects #7

“Reports about Practical Projects” are written by doctoral researchers who have designed and carried out a practical project in cooperation with a non-university organization. The BGHS has been supporting these projects with scholarships since 2020. In the seventh part of the series, Gladys Vasquez Zevallos reports on her practical project with the Kuskalla Abya Yala.

As stated by the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, although indigenous people represent less than 6% of the world’s population, they speak more than 4,000 of the world’s approximately 6,700 languages. This statistic shows that most indigenous languages are under the threat of Language Loss. One of the main reasons for this is that throughout state formation, states implemented integration policies, especially in education, which ended up being assimilation policies. This policy meant the imposition of Western values, one of the most notable cases being the imposition of a unitary language that reinforced discrimination against indigenous nations, their culture, and languages. However, in recent years there has been a growing movement for recovering the indigenous language based on revitalization practices. These are practices to foster new speakers when the intergenerational transmission of the language has been interrupted. For this reason, I organized, in collaboration with Kuskalla Abya Yala, a workshop dedicated to the practices of the revitalization of native languages, focusing on the case of the Quechua language. Kuskalla Abya Yala is a non-governmental organization primarily devoted to the revitalization of the native languages of Quechua. Indeed, Quechua is the most widely spoken Indigenous language family in America; 7 to 9 million speakers.

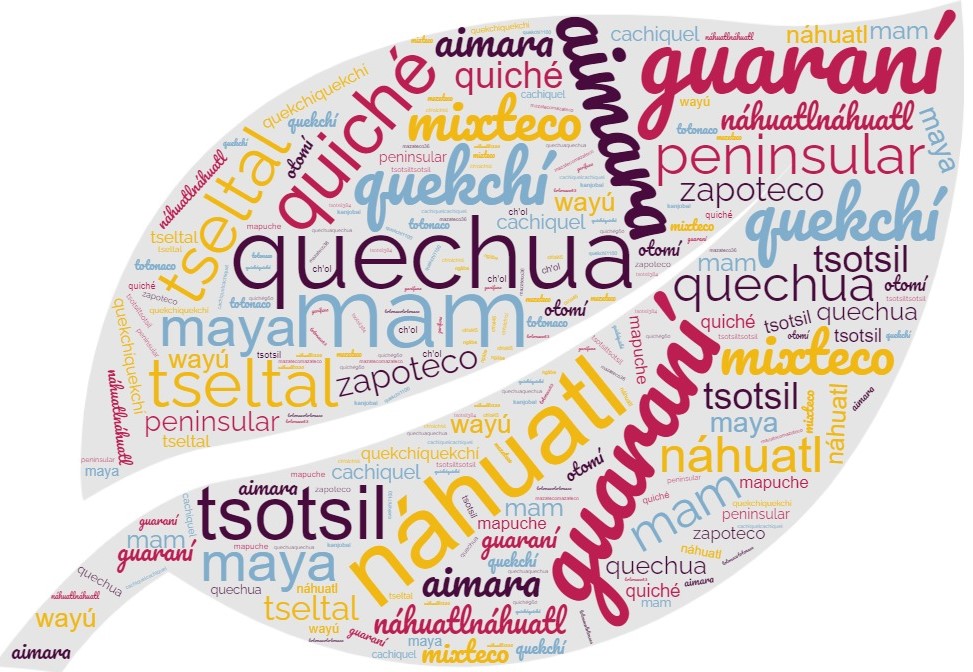

Image 1: Most spoken indigenous languages © Gladys Vasquez

Kuskalla has implemented free educational programs through technological opportunities while building international solidarity networks. Thus, the workshop’s purpose was to share the experience of different actors with diverse intellectual backgrounds in diffusing the Quechua language in two main aspects: Reflection on post-colonial structures in the production of indigenous knowledge and alternative experiences of visualization and dissemination of the Quechua language. The workshop was divided into two days, and the results were directly related to strategies for disseminating indigenous knowledge outside the educational spaces that have historically promoted linguistic discrimination.

One of the primary reflections was on the stereotypes surrounding indigenous languages and how to see them as something of the past. Indigenous communities are perceived as timeless when adaptation and migration have been their constant feature. Another reflection was that Indigenous languages are not only used for communication but also as a system of knowledge, history, memory, and identity. Much of the discussion was on how the Quechua people are revitalizing their language while recovering their identity.

All this is thanks to different practices in rural and urban areas using their educational pedagogies, music, artistic representations, and media. While many of these initiatives began, especially in the Andes, many indigenous immigrants in the United States are now promoting the Quechua language in academia and community groups. In the United States, it is the most widely taught indigenous language in universities, with approximately fifteen programs. The basis of these programs is partnerships with indigenous organizations. In this sense, the workshop promoted the creation and strengthening of networks among the actors that disseminate knowledge of the indigenous world.

Click here for Kuskalla Abya Yala.

Further information about the Non-University Careers Project can be found on the BGHS website.