Center for Uncertainty Studies Blog

Christian Wachter, Thinking in Connections: Embracing Uncertainty as Freedom

A Short Conference Report on “ACM Hypertext 2023”

In the heart of Rome, a city woven with numerous layers of history and tales, the 34th Association for Computing Machinery's conference on Hypertext and Social Media found its perfect backdrop last September.1

This is because Rome mirrors the essence of hypertext that is commonly defined as a dynamic web of interconnected information nodes, allowing for unlimited growth and flexible formation of new interconnections over time – just like Wikipedia or the World Wide Web. Rome’s vast wealth of monuments has also been considered in ever-new constellations. Think of ancient monuments such as the Colosseum, the Hippodrome, or the Pantheon that were erected in different periods but today symbolize the ancient heritage of Roma Aeterna. The Middle Ages, Early Modern, and Modern times reshaped the city’s surface and led to new functions and perceptions of older monuments within the now-grown network of architectural heritage. Take the Colosseum, once a grand amphitheater, evolving over centuries to serve new roles from provisional housing in early medieval times to a consecrated martyr site in the 18th century. This development situated the Colosseum into the city’s ensemble of Christian sites.

This notion of flexibility, of contingent possibilities to arrange information and form meaning, summarizes the spirit of the five-day workshop and conference program at the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max Planck Institute for Art History. Here, hypertext was explored through different lenses: Workshops delved into “Human Factors in Hypertext,” “Narrative and Hypertext,” “Open Challenges in Online Social Networks,” “Web/Comics,” and “Legal Information Retrieval meets Artificial Intelligence.” The conference tracks were dedicated to “Interactive Media: Art and Design,” “Authoring, Reading, Publishing,” “Workflows and Infrastructures,” “Social and Intelligent Media,” and “Reflections and Approaches.” Altogether, this marks a rich tapestry that might seem to lack coherence at first glance.

But far from that, researchers from all over the world discussed hypertext not only as a concept for (digital) infrastructure, network media, or non-linear narratives. Instead, hypertext was broadly addressed as a mode of thinking, as Dene Grigar (Vancouver, USA) emphasized in her workshop keynote on Hypertext Art and editing systems. She illustrated how hypertext literature, video games, and other non-linear art formats are products of thinking in connections. Readers/Users do not precisely know where the multifaceted storytelling brings them. They must find their own paths through the network of possible constellations through interactive navigation. This exploration of uncertainty is not merely a byproduct but a deliberate design, because authors thereby communicate that multiple layers of meaning and possibility exist. The conference participants delved into that experience through a wonderful exhibition Grigar and her team set up in place – Hypertext & Art: A Retrospective of Forms.2 It showcased many early hypertext art pieces running on original hardware and digitized works, thus offering a tangible connection to the conference discussions.

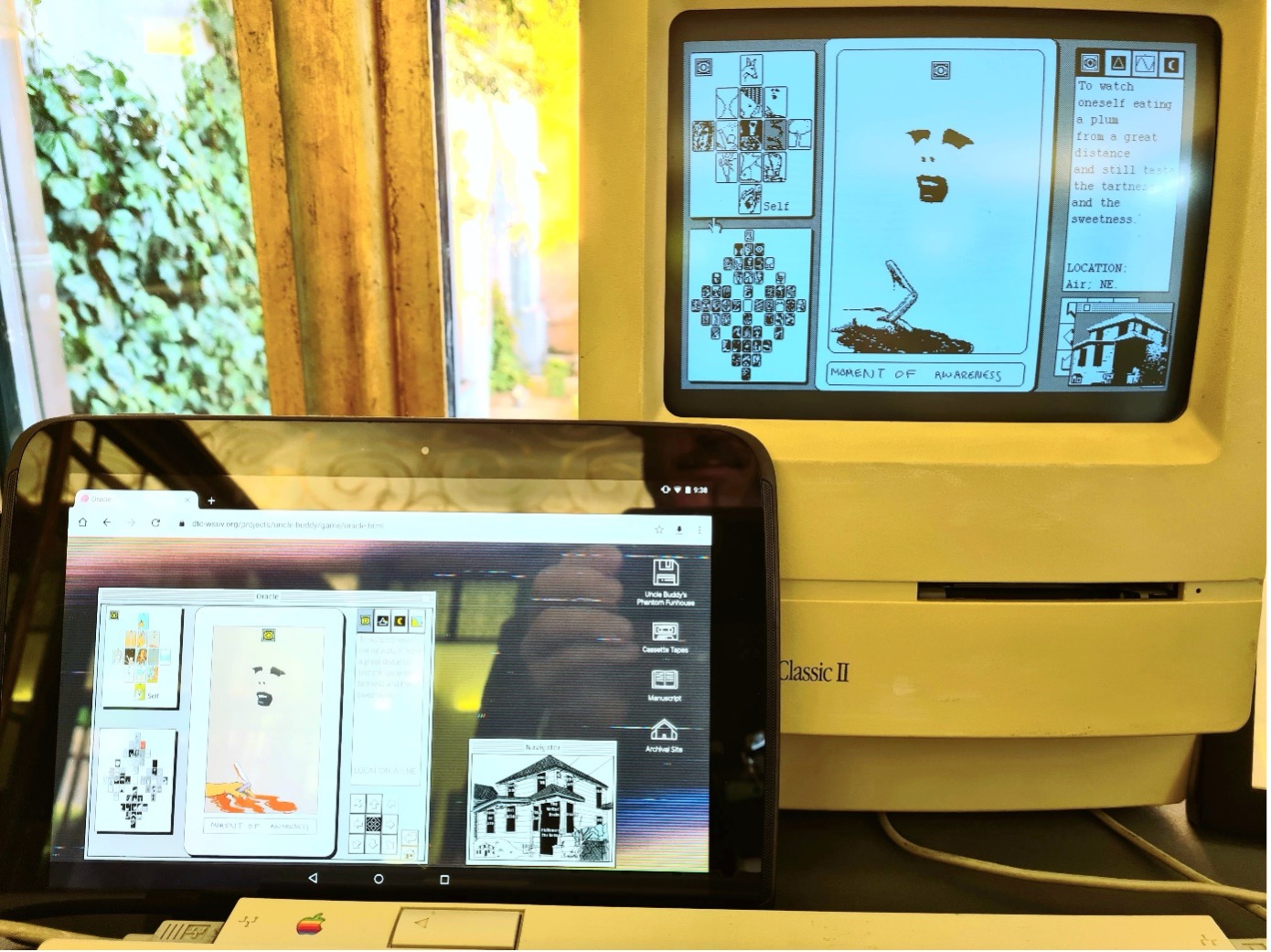

The exhibition Hypertext & Art: A Retrospective of Forms, curated by Dene Grigar.

1992/93 hypertext novel and game Uncle Buddy's Phantom Funhouse, running on an Apple Classic II and emulated on a tablet computer. This double setup provided both, an original user experience and a modern adaptation for the touch screen.

Media formats and editing tools beyond the rather linear design of traditional texts were subject to many other presentations, and I can only give a glimpse of the rich conference program here. Among the plethora of ideas and projects, one notable example was SPORE, introduced by Daniel Roßner (Hof), Claus Atzenbeck (Hof), and Sam Brooker (London). This tool offers a canvas for authors to craft stories by arranging information blocks in a visual user interface.3 SPORE reads these spatial constellations and dynamically suggests new story elements, powered by AI technologies. The tool thus supports authors in finding and forming stories in an iterative – in that sense uncertain – process. Frode Hegland (Southampton) also emphasized hypertextual media as tools for thought with a maximum of freedom.4 This becomes accelerated in Virtual Reality (VR) environments, which Hegland characterized as “anthropological interfaces.” Drawing inspiration from hypertext pioneer Douglas Engelbart, Hegland characterized hypertext as a tool that augments human intellect – a theme echoed throughout the conference. As one further example in this context, Serge Bouchardon (Compiègne) elaborated on fictional stories for smartphones that work by messaging and notifications.5 These hypertext adaptations create an interactive experience intertwining with our daily digital routines and, in doing so, playing with concepts of time for narratives.

The conference threads wove through themes of freedom, complexity, and multivocality as productive alternatives to rigid structures of information organization. The keynotes6 covered various fields of application for that: Harith Alani (Milton Keynes) focused on tracing sources of misinformation and its proliferation through social media in his keynote on Fact-Checks vs Misinformation. Untangling these complex networks becomes possible through knowledge graph technologies. Identifying biases in AI-generated content was one focus of Jill Walker Rettberg’s (Bergen) keynote on Feral Hypertext Redux, whereas Aldo Gangemi (Bologna) addressed Perspectival Modelling of Human-Centred Knowledge with its network-like patterns. Identifying and highlighting intricate patterns was also applied to historical studies. Megan Bushnell (London) elaborated on medieval books as "organized hypertextuality."7 Scholarly editions and translations should respect and unveil networks of information inside the books. Christopher Ohge (London) expanded on this notion by presenting a digital edition project on Mary-Anne Rawson’s anti-slavery anthology The Bow in the Cloud.8 Jamie Blustein (Halifax, Canada) shifted the spotlight from text to artwork, introducing the H.A.I.K.U. Touch Archive Project that allows scholars to explore elements of artwork and annotate them in space.9

Bridging the boundaries of media with hypertext was another popular topic at the conference. Transmedia storytelling combines multiple media in one overarching narrative experience. This moves stories into mixed realities, as Valentina Nisi (Funchal/Lisbon) put it in her workshop keynote, and is being applied in diverse areas such as tourism, history, or museums. Emily Norton (Tampa) brought geographic elements into play by introducing a digital adaptation of James Joyce's Modernist novel Ulysses. It employs hypertext annotations, an interactive map, and wiki technology, to provide contemporary readers with easier access to Joyce’s text.10

To be sure, the conference’s 2023 edition covered many more hypertext-related issues – more than I can report in detail here. The rich tapestry of paper topics spanned from further applications of VR, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Social Media methods and content analysis, linked (open) data, games, and locative storytelling, to the history of hypertext. My own contribution focused on revisiting scholarly hypertext.11 It argued that hypertext allows (digital) humanities scholars to craft publication formats that transparently communicate epistemic dimensions of their research in terms of multiperspective demonstrations. When hypertext is visualized – thus multimodal or spatial hypertext – this potential is accelerated because the visual representation unveils the non-linear architecture of argumentation, narrative, and (in the case of data-driven research) data interpretation.

Despite the broad range of topics and approaches, I felt at just the right place to present my work, get inspiration from the community, and engage in stimulating discussions. This is in large part due to a warm-welcoming and highly communicative community, which made it easy to connect. United by a common vision of hypertext as a foundational tool for interconnected thinking, we embraced the complexities and contingencies inherent in our work, viewing these notions of uncertainty not as obstacles but as productive pathways to new perspectives and insights.

Let me end with a remarkable story from the history of the conference. It is an anecdote of uncertainty in itself. For the 1991 edition in San Antonio, Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau submitted a paper to present a nascent project they have been working on at the CERN for two years: the World Wide Web. Their paper was rejected and a live demonstration Berners-Lee and Cailliau managed to set up at the venue did not spark much interest. The WWW was deemed too simplistic.12 Yet, as it would soon blossom into the foundational fabric of our digital world, this story is a vivid reminder that the seeds of transformative ideas often lie in unexpected places.

References

1) https://ht.acm.org/ht2023/

2) For an online version of the exhibition visit: https://the-next.eliterature.org/exhibition/hypertext-and-art/.

3) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609075

4) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609036

5) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609081

6)https://ht.acm.org/ht2023/programme/keynotes/

7) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609074

8) https://christopherohge.com/the-making-of-an-anti-slavery-anthology-mary-anne-rawson-and-the-bow-in-the-cloud/

9) https://web.cs.dal.ca/~jamie/HAIKU/

10) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609051

11) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3603163.3609072

12) https://first-website.web.cern.ch/node/25.html